Some Opportunities and Challenges of Electronic Justice

Introduction

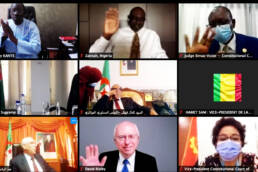

The use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in ensuring access to justice and the administration of the law or e-justice has become increasingly meaningful during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the outbreak of the deadly virus, justice institutions and individuals administering the law from numerous countries around the world including those in Africa have been encouraged to use digital means to administer law and justice. For instance, the former Honorable Chief Justice David Maraga of Kenya launched an e-filing system for Kenya’s judicial system in mid-2020. In addition, the Honorable Chief Justice Bart M. Katureebe of Uganda issued a circular in March 2020 directing, among other things, the possibility of conducting proceedings via video link. In South Africa, the Office of the Chief Justice issued a direction in April 2020 for hearing to be conducted via videoconference and for parties to file their heads of arguments electronically.

It is not only during times of crisis that e-justice becomes beneficial but it is also useful during normal circumstances. Jurisdictions that have used e-justice including court automation, online proceedings, online mediation, and etc., prior to the COVID-19 pandemic have revealed some positive contributions. E-justice has been particularly useful to the actors especially the courts, prosecution, lawyers, and the parties involved. Despite the opportunities e-justice presents, it is not immune to challenges. Entities that have used the e-justice system also experienced some challenges that require constant improvement.

The following are some opportunities and challenges facing e-justice and some thoughts to consider in improving the e-justice system.

1. Opportunities/Positive contributions of E-justice

E-justice as we know it, is a subset of the general notion of e-government, which is intended for efficient and effective delivery of government services to its citizens. In the context of e-justice it is intended for a number of reasons including effectiveness and efficiency in access to justice and the administration of law. This is true for some countries including Turkey, Italy and Mexico who shared their national experiences in a 2016 panel discussion organized by that United Nations in New York on the subject matter. They all alluded to the fact that e-justice has saved them money and time which contributed to the timely delivery of justice. The timely delivery of justice also means that there will be lesser case backlogs and bottlenecks. We know that backlogs can be a problem created by the system and e-justice tends to rectify this challenge. Such was the case witnessed in Singapore, which is one of the first countries in the world to use e-justice in the early 1990s to solve its case backlogs. In addition, it is believed that e-justice can contribute to improved accountability and transparency and tends to minimize corruption. Some see its potential in achieving social and economic development as expressed by Uganda’s Minister for Justice and Constitutional Affairs, Hon. Prof. Ephraim Kamuntu, during an on-line dialogue on the future of e-justice hosted by UNDP in May 2020. He expressed that the transformation of the country and achievement of a middle class-income status are dependent upon a strong judiciary and competitive economy premised on ICTs and innovations.

Furthermore, for the general public, it makes access to information easier thus contributing to the transparency of the judicial system. One can access information and monitor the progress of proceedings, legal databases and judgements which can be an opportunity for public awareness and scrutiny of the judicial system. A progressive and healthy system is one that is objective and open to scrutiny, which can then can contribute to improvements of the system.

In addition, the encouragement and use of e-justice is a paperless process, which can contribute to the achievement of environment conservation goals including curbing deforestation and terminating global climate change.

E-justice serves to foster the overall notion of the rule of law, and in particular the procedural rights of access to information, public participation and access to justice, which are enshrined in the general principles of law, both soft and hard law. A regional convention that speaks directly to this cause is the Aarush Convention of 1998 (UNECE Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters). The Aarush Convention addresses issues of accountability, transparency and responsiveness concerning environment matters. Furthermore, two soft law instruments, Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration of 1992 and UNEP Bali Guidelines of 2011 are dedicated to these procedural rights. Although soft law instruments are non-legally binding, they impose a very high moral standard on the subjects it is intended for.

On the overall e-justice encompasses numerous positive traits and thus has much more to contribute in furtherance of the rule of law, access to information, public participation in decision making and access to justice.

2. Challenges of E-justice

While e-justice presents opportunities and embraces some positive characteristics, it is not immune to challenges. Those that have been using the system still face hurdles that require constant investment of time and resources for improvements. The first and foremost challenge especially for the African region is the issue of digital divide. Many countries in Africa possess inadequate ICTs infrastructure that would allow citizens to access the e-justice system. E-justice is widely dispersed in the region. This means that many people do not have access to e-justice. Figures released by World Internet Stats in March 2020 reveals that internet penetration in Africa varies from one country to another. Kenya ranks the top with 87.2% accessibility and the South Sudan at the bottom with 7.9 % accessibility. The rest of the countries are in between with most ranking below 50 % accessibility. The accessibility challenge can be coupled with issues of ICTs illiteracy. Furthermore, from an environmental justice perspective, ICTs and e-justice can be a luxury for many underprivileged and poor people/communities who cannot afford the technology meaning they will miss out on the e-justice system and consequently be denied access to justice. From interviews conducted by the Environmental Justice Project in EU in 2003 – 2004, 97 % of the practitioners and NGOs interviewed in England and Wales mentioned that there is no access to justice in civil cases. While this is true for access to justice in traditional court settings, one can imagine more challenges being faced when it comes to the e-justice system.

A second and related challenge can be the issue of language. For those that are literate, it might be easier to access the e-justice system without much difficulty, but for the illiterate ones it can impinge upon their understanding and subsequently impact their opportunity for access to justice.

A third challenge for e-justice or ICTs especially the internet or databases that store data is the issue of security. The internet or databases handles sensitive information and it is prone to attack by hackers who may steal or destroy crucial information.

A fourth challenge has been that in a same jurisdiction especially for federal systems, e-justice systems have been developed in isolation using varying standards. The systems were developed without much coordination from a centralized point thus generating varying information that can cause confusion at the national level. This was the case of Brazil.

Some Final Thoughts

– For e-justice to be used more widely, effectively and efficiently, enabling environments especially investment in ICT infrastructure is crucial, and this can help narrow the digital divide facing many countries today. Governments and justice institutions must continue to invest more in e-justice infrastructure. This would also mean the training of specialized staff to be able to guide and assist the users.

– Not many are accustomed to using e-justice, therefore governments and justice institutions must institute certain social and behavioral changes, especially education (both formal and informal), awareness raising and capacity building to help people understand how the e-justice system functions.

– The e-justice system must be user-friendly to ensure that not only immediate users of the e-justice system, but the general public especially the underprivileged and poor must be able to access and use the system easily. Such a system will be seen to deliver on environmental justice.

– The standardization of the e-justice system within the same jurisdiction must be encouraged to avoid confusion. This will then contribute to the smooth delivery of access to justice.

– Justice institutions should build secure and safer systems to protect sensitive information stored in databases or build back-up systems so as to maintain safely sensitive information or data.